Friends

The Power of Fake Gay (and Black) Friends

How fiction changes the world.

Posted June 20, 2012

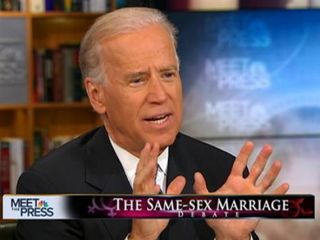

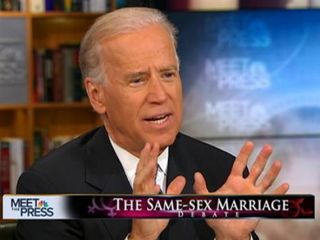

The “evolution” of President Obama’s views on same-sex marriage match the rapidly liberalizing attitudes of the country as a whole. The swift pace of change has flummoxed social scientists, who expect much slower erosion of entrenched cultural biases. On the May 6th episode of Meet the Press, Joe Biden surprised viewers not only by endorsing gay marriage himself, but by attributing historic changes in American views of homosexuality to the sit-com Will and Grace.

The Daily Show

The Daily Show

Cameron and Mitchell from Modern Family

Research shows that regular contact with homosexual friends or family members is a better predictor of gay-friendly attitudes than gender, level of education, age, and even political or religious affiliation. And the same seems to be true for the illusory relationships we form with fiction characters. We relate to the characters on Friends, in other words, as though they were our real life friends. When we are absorbed in fiction, we form judgments about the characters exactly as we do with real people, and extend those judgments to the generalizations we make about groups. When straight viewers watch likeable gay characters on shows like Will and Grace, Modern Family, Glee, and Six Feet Under they come to root for them, to empathize with them--and this seems to shape their attitudes toward homosexuality in the real-world. Studies indicate that watching television with gay friendly themes lessens viewer prejudice, with stronger effects for more prejudiced viewers.

The implications of these studies extend beyond the issue of homosexuality and bias. For example, if you are white and you make a black friend, your prejudice is likely to diminish. And the same thing happens if you make faux black friends with the characters on The Cosby Show or Everybody Hates Chris. All of this research adds up to a surprising possibility: fiction characters from Will and Jack, to the big screen characters played by Sidney Poitier and Denzel Washington, to the protagonists of novels like Roots and Uncle Tom’s Cabin, may have improved the lot of American minorities as much as direct political action has.

Stories change us, and through us, they change the world. In the middle of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln greeted Harriet Beecher Stowe at the White House, saying, "So you're the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war." Lincoln went a little far in his flattery, but historians agree that Uncle Tom’s Cabin, exerted a momentous impact on American culture, inflaming passions that helped bring on the most terrible war in our history.

Sometimes the change is mainly for the better, as with Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Will and Grace. Often it’s for the worse, as when the Klan-glorifying film Birth of a Nation (1915) gave new life to a moribund KKK, or when the heroic violence of the Iliad helped inspire Alexander the Great’s gory pursuit of immortal fame (as the novelist Samuel Richardson asks: “Would Alexander, madman as he was, have been so much a madman, had it not been for Homer?”). And sometimes fiction’s historical effects remain ambiguous. For instance, Ayn Rand novels like The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged have spread an ethic of hard-core individualism through American culture, inspired the Tea Party, influenced the Federal Reserve (Alan Greenspan was a Rand disciple), and made the rise of politicians like Ron and Rand Paul possible.

How can fiction—the fake struggles of fake people—transform the real world? Until recently we have had no idea. But in the last several decades psychology has begun a serious study of story’s effects on the human mind. Fiction teaches us facts about the world, influences our morals, and marks us with fears, hopes, and anxieties that alter our behavior. As the psychologist Raymond Mar writes, “Researchers have repeatedly found that reader attitudes shift to become more congruent with the ideas expressed in a [fiction] narrative." In fact, fiction seems to be more effective at changing beliefs than non-fiction, which is designed to persuade through argument and evidence.

What is going on here? Why are we putty in a storyteller’s hands? The psychologists Melanie Green and Tim Brock argue that entering fictional worlds “radically alters the way information is processed.” Green and Brock’s studies shows that the more absorbed readers are in a story, the more the story changes them. Highly absorbed readers also detected significantly fewer “false notes” in stories—inaccuracies, infelicities—than less transported readers. Importantly, it is not just that highly absorbed readers detected the false notes and didn’t care about them (as when we watch a pleasurably idiotic action film). They were unable to detect the false notes in the first place.

And, in this, there is an important lesson about the molding power of story. When we read non-fiction, we read with our shields up. We are critical and skeptical. But when we are absorbed in a story we drop our intellectual guard. We are moved emotionally and this seems to leave us defenseless. Anecdotes about those rare ink people—like Rand’s John Galt or Stowe’s Uncle Tom--who vault the fantasy-reality divide to change history are impressive. But what is more impressive, if harder to see, is the way our stories are working on us all the time, reshaping us in the way that flowing water gradually reshapes a rock.

Put another way, new research doesn’t just suggest that fictitious gays blazed the trail that led to Barrack Obama’s historic endorsement of gay marriage. It suggests that but for “fictitious blacks”—from Kunta Kinte to the powerful African American commander-in-chief on the television show 24—we might not have had a President Obama in the first place.

Jonathan Gottschall is the author of The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human