Diet

Strengthening Ties that Bind: Weight Control

What determines who are the people successful at weight loss and maintenance?

Posted October 10, 2012

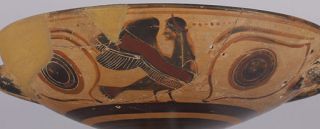

Ancient Greek red figure pottery showing Odysseus tied to the mast.

In Book XII of Homer’s Odyssey, the sorceress Circe tells Odysseus of the dangerous but enchanting sound of the Sirens. “There is a great heap of dead men’s bones lying all around, with flesh still rotting off them,” for those who don’t heed her warning about the lure of their singing. She cautions that Odysseus put wax in his men’s ears, but if he wants to hear their extraordinary song for himself, his men must tie him to the mast of their ship. And if he begs for them to untie him, they must bind his cords more tightly. The story has been depicted in art throughout the ages, including on Greek black figure and red figure pottery and a 19th century painting by English artist John William Waterhouse, “Ulysses and the Sirens.”

The theme of Odysseus (Ulysses) tied to the mast is a popular one in classical art.

Metaphorically for some, the lure of food has the same effect as the Sirens’ song and our “obesogenic” environment, the same potentially deadly consequences. Pratt and Wardle, in a recently published article in the International Journal of Obesity, revisit the concept of dietary restraint and self-control to distinguish when restraint may lead to “effective weight control” and when it might lead to undermining that control. They explain that so-called “restraint theory” for years held that restraint in eating led to “counter-regulatory responses,” reduced ability to monitor satiety, and even “dis-inhibited, binge-like eating patterns.” On the other hand, those who were more “relaxed” about food were more likely to have better weight control, healthier eating patterns, and even a better body image. The problem, say Pratt and Wardle, is that restrained eaters are not a homogeneous group and some are more vulnerable than others to succumbing to their food temptations. In other words, some dieters find restraint ineffective and even counterproductive and prefer what is called an “undieting,” approach; others find using restraint a helpful cognitive means for maintaining control of their food intake. Furthermore, researchers can break down dietary restraint into “rigid” restraint (i.e., with an “all-or-none approach to weight control) and “flexible” restraint (i.e., a “more graduated” approach such that some tempting foods can be eaten in small quantities while compensating by eating less of other foods) as long as the person doesn’t cross his or her own “eating boundary.” What distinguishes successful restrained eaters from unsuccessful ones? Pratt and Wardle report that successful restrained eaters are able to respond to food cues by being able to think long-term and focus on a ‘dieting’ goal” whereas those not successful activate a more immediate pleasurable ‘eating’ goal. These authors acknowledge that genetics likely plays a role in determining differences among those dieters who can exert more self-control from those who have more difficulty.

Along those lines, Lorraine G. Ogden and her colleagues, writing recently in the journal Obesity, found four distinct subgroups among their successful dieters in their National Weight Control Registry. This ongoing “observational” study, begun in the early 1990s has followed over 5000 self-referred dieters who have been able to lose at least 30 pounds and keep the weight off for at least a year (and most, for much longer.) In previous publications, the researchers who began the study have described that successful dieters, in general, were more likely to eat breakfast regularly, exercise about one hour a day (mostly walking) and expend 1000 to 2000 calories/week, monitor their weight and continue to do so even during weight maintenance, eat low calorie, lower fat foods, and maintain diet consistency not only on weekdays but also weekends and holidays. In this most recent article, the authors studied over 2200 participants from their larger sample. They found that about 50% of their sample fell into Cluster 1, “a weight-stable, healthy, exercise-conscious group who are very satisfied with their current weight.” Almost 27% fell into Cluster 2, a group who have “continuously struggled” with their weight since they were children, required the most resources and strategies to lose and control their weight, and experienced greater levels of stress and depression. Almost 13% fall into Cluster 3, a group who are successful with weight control on their first try, (“participants with immediate and long-term success”) more likely to have maintained their weight loss for the longest time, have the least difficulty with weight control, and least likely to have been overweight during childhood. Almost 10% fall into Cluster 4, a group who tend to be older, eater fewer meals, less likely to exercise to control their weight, and more likely to have health difficulties.

Bottom line: Even among those successful at weight loss and maintenance over time, “one size does not fit all” and some will struggle more with the process than others, whether with food restraint specifically or weight maintenance in general.