Neuroscience

The Neuroscience of Social Pain

Social pain activates the same brain circuitry as physical pain.

Posted March 3, 2014

Neuroscientists in Italy have discovered that “social pain” activates the same brain regions as physical pain. The researchers also found that witnessing the social pain of another person activated a similar physical pain response of empathy in most test subjects.

Social pain is caused by events such as feeling excluded from social connections or activities, rejection, bullying, the sickness or death of a loved one, a romantic break-up…

The new study found that social pain activates similar brain circuits whether someone was suffering personally or if they experienced the pain as an empathic response to another person's social pain. From an evolutionary standpoint, these pain responses protect the individual but also fortify social connectivity which protects the collective.

The February 2014 study titled, “Empathy for Social Exclusion Involves the Sensory-Discriminative Component of Pain: A Within-Subject fMRI Study” from the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) of Trieste was published in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.

This new study by Dr. Giorgia Silani and colleagues is innovative because it adopted a more realistic experimental procedure than was used in past experiments that compared physical and social pain. Silani said, "Classic experiments used a stylized procedure in which social exclusion situations were simulated by cartoons. We suspected that this simplification was excessive and likely to lead to systematic biases in data collection, so we used real people in videos."

"Our data have shown that in conditions of social pain there is activation of an area traditionally associated with the sensory processing of physical pain, the posterior insular cortex," explains Silani. "This occurred both when the pain was experienced in first person and when the subject experienced it vicariously."

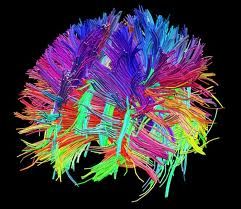

The Insular Cortex (Insula)

In each hemisphere of the cerebrum the insular cortex (also called the insula) is an “island” of brain matter about the size of a kumquat folded into the cerebral cortex. The insular cortex is divided into two parts: the larger anterior insula and the smaller posterior insula. The insulae have long been associated with consciousness, emotion and the regulation of the body's homeostasis. Other functions of the insular cortex include perception, motor control, self-awareness, cognitive functioning, and interpersonal connectedness.

These new findings support an October 2012 study published in the journal Brain titled “Anterior Insular Cortex Is Necessary for Empathetic Pain Perception.”

Silani concludes, “Previous neuroimaging evidence suggests that observing others’ suffering and pain elicits activations of the anterior insular and the anterior cingulate cortices associated with subjective empathetic responses in the observer. Our findings lend support to the theoretical model of empathy that explains involvement in other people's emotions by the fact that our representation is based on the representation of our own emotional experience in similar conditions."

The Brain Science of Empathy

Previous research on the brain science of empathy has indicated that the threat of pain to oneself is directly correlated to the brain regions of a threat of pain to a loved one—but not as strongly when the threat of pain is to a stranger. In August of 2013, I wrote a Psychology Today blog post about this phenomonen titled “Neuroscientists Confirm That Our Loved Ones Become Ourselves.”

The ability to put yourselves in another person’s shoes at a deep neurobiological level may depend on whether the person is a stranger or someone you know. The study titled "Familiarity Promotes the Blurring of Self and Other in the Neural Representation of Threat" appears in the August 2013 issue of the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.

According to researchers, the human brain puts strangers in one bin and the people we know in another compartment. People in your social network literally become entwined with your sense of self at a neural level. "With familiarity, other people become part of ourselves," said James Coan, a psychology professor in University of Virginia's College of Arts & Sciences who used functional magnetic resonance imaging brain (fMRI) scans to find that people closely correlate people to whom they are attached to themselves.

Humans have evolved to have our self-identity become woven into a neural tapestry with our loved ones. James Coan concluded, "Our self comes to include the people we feel close to. This likely is because humans need to have friends and allies who they can side with and see as being the same as themselves. And as people spend more time together, they become more similar.”

The Neurobiology of Psychopathy

Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterized by ‘a lack of empathy and remorse, shallow affect, manipulation and callousness.’ When individuals with psychopathy imagine others in pain, researchers have found that brain areas necessary for feeling empathy fail to become active and connected to other important regions involved in affective processing and compassionate decision-making.

A September 2013 study from the Department of Psychology at the University of Chicago published in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience found the neurobiological roots of psychopathic behavior also linked to the insular cortex and other brain regions associated with pain perception.

The increase of activity between certain brain circuits linked to pain were unusually pronounced in psychopaths. The researchers found that highly psychopathic people can be very sensitive to the thought of their own pain but there was a brain short-circuit that made them unable to empathize with another person’s social or physical pain.

When participants imagined pain to others, these regions failed to become active in high psychopaths. In a sadistic twist, when imagining others in pain, psychopaths actually showed an increased response in the ventral striatum, an area known to be involved in pleasure. Based on this assessment, the participants were divided into three groups: highly, moderately, and weakly psychopathic.

In the study participants were shown a variety of visual scenarios illustrating physical pain, such as a finger caught between a door, or a toe caught under a heavy object. Then they were asked to imagine that this accident happened to themselves, or somebody else. They were also shown control images that did not depict any painful situation, for example a hand turning a doorknob.

When highly psychopathic participants imagined pain to themselves, they showed a typical neural response within the brain regions involved in empathy for pain, including the anterior insula, the anterior midcingulate cortex, somatosensory cortex, and the right amygdala. The same regions did not light up when they witnessed the suffering of another person.

Conclusion: Mindfulness Meditation Can Alter the Insula

There is emerging evidence which suggests that the insula can be reshaped and rewired through loving-kindness and mindfulness meditation. Neurons in the insula can literally become bulked up and better connected through mindfulness which can improve the empathetic response of the insula.

The insula functions at a high level of automatic control, which means that it can benefit through consistent and rigorous daily mindfulness training. Research has found that various types of mindfulness meditation create brain changes linked to a more automatic response of compassion, loving-kindness and empathy for other people's suffering. Compassion can be trained.

Current methods for studying changes in specific brain areas—like the insular cortex—through mindfulness meditation are still in their infancy. That said, daily habits that include mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation most likely alter the structure and function of the insula and have the ability to enhance empathy at a neural level.

If you'd like to read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts:

- “Neuroscientists Confirm That Our Loved Ones Become Ourselves"

- "Can Meditation Make Someone More Compassionate?"

- “The “Love Hormone” Drives Human Urge for Social Connection"

- “The Neuroscience of Empathy”

- “Maintaining Healthy Social Connections Improves Well-Being”

- “Social Connectivity Drives the Engine of Well-Being”

- “How Does Meditation Reduce Anxiety at a Neural Level”

- “Optimism Stabilizes Cortisol Levels and Lowers Stress”

- “Positive Actions Build Social Capital and Resilience”

- "The Neurobiology of Grace Under Pressure"

- "Do 'Mirror Neurons' Help Create Social Understanding?"

- “Compassion Can Be Trained”

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.