Stress

Youngest Serial Killer on Death Row

How might the movement toward leniency affect this killer's case?

Posted July 3, 2012

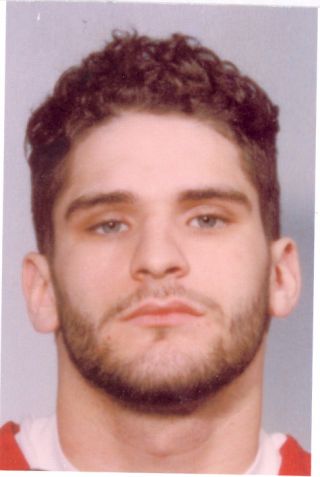

Tales of serial killers have grown commonplace, but adolescent serial killers are rare. Harvey Robinson from Allentown, PA, is among them, and he’s currently the youngest contemporary serial killer to be sent to death row in America. His case crystallizes some issues surrounding a growing trend toward leniency with juvenile offenders, even the most violent ones.

In Roper v. Simmons (2005), the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the death penalty for offenders who had committed extreme crimes when they were juveniles. In Graham v. Florida (2010), the Court outlawed life without parole sentencing for juveniles convicted of non-homicide crimes. The decision was based in part on neurological research that demonstrated that adolescents are more impulsive and more susceptible to negative influences than adults; mentally and emotionally, their brains are immature. On June 25, 2012, the Court took another step and abolished all mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles convicted of homicide.

Also in June, the citizens of Allentown collectively held their breath as Harvey Robinson went before a judge to request new sentencing, based on undetected brain damage implicated in his crimes. If the judge were to decide in his favor, they knew, he could chip at the eroding wall that stands between him and possible freedom one day.

In less than a year in 1993, Robinson attacked five females, killing three. He was just 17 years old when he committed his first murder.

He spotted this victim through her window as she undressed for bed. He broke in and killed her. Then after a brief stint in a juvenile facility for a burglary, he grabbed a fifteen-year-old girl off her bike, raped her, and stabbed her twenty-two times.

Six weeks later, Robinson entered another home, but saw his targeted victim with her boyfriend, so he attacked her five-year-old daughter, raping and strangling her. She was found unconscious but miraculously alive.

Soon thereafter, Robinson chased down a woman as she tried to flee from him. He caught up and was raping and choking her when a neighbor switched on an outside light, scaring him away. Aware that he’d left a living witness, he soon entered her home again, but she was not there.

The police believed he would return, so they implemented a risky plan to trap this killer, knowing he would continue until he was stopped. Bravely, the victim agreed to act as bait. In the meantime, Robinson had raped and strangled another woman.

Yet he’d not forgotten the one who got away. He broke in once more, but an officer was waiting for him. After a desperate gunfight, Robinson was caught.

During Robinson’s trial, a forensic psychiatrist testified that he suffered from a dependency on drugs and alcohol and had experienced visual and auditory hallucinations, which had made it difficult for him to adjust to social norms. He’d been under severe stress. Because he had a violent role model in a criminal father, he’d understandably relieved his stress with violence. The psychiatrist believed that, with help, Robinson could overcome his violent impulses.

However, Robinson did not just make an immature mistake; he was a cold-blooded rapist and killer, returning again and again to ensure that his targeted victims were dead. He even tried killing a child.

To the relief of many in the community, on November 8, 1994, Robinson was convicted on three counts of murder and sentenced to death three times.

A new attorney challenged his convictions on the grounds that there were fundamental flaws in the trial procedures. Robinson got his day in court, but he wasted it complaining about his former lawyers.

Still, in 2001 a judge vacated two of Robinson’s death sentences and ordered new hearings. Four years later, the Supreme Court abolished the death penalty for juveniles age 17 and under. This ruling commuted Robinson's remaining death sentence to life. He knew he had a chance to get off death row.

To prepare for the new sentencing hearings, Robinson’s attorneys had neurological testing performed. The results, they claimed, showed that Robinson had suffered from frontal lobe damage at the time of the murders, which had adversely affected his ability to control his behavior.

However, as the survivors and victim’s families hoped, the judge who listened to Robinson’s new argument decided against him. He had failed to prove that these tests had shown brain damage dating back so many years. This decision restored one death penalty, which will make it more difficult for Robinson to use this reasoning during the next round (next March).

He probably won’t give up. He has many years yet in which to make arguments and await advances in neuroscience. However, for now, the threat of any argument for leniency or eventual parole has been defused. Robinson remains the youngest serial killer on death row.