Sex

Much Ado About Sex Differences In Reproductive Success

Sex, fertility, and the origins of evolved human mating strategies

Updated July 15, 2023

One of the top science stories of 2012 (according to Discover magazine) was a study of fruit flies conducted by UCLA’s Patricia Gowaty and her colleagues. In their research labs, they tried (and failed) to replicate one of the classic studies of all time in biological science: Bateman's (1948) research showing males of Drosophila melanogaster have higher variance in reproductive success (RS) than do females of the species. Bateman originally found some fruit fly males tend to reproduce a lot, whereas others find themselves completely shut out of reproduction. Most fruit fly females, in contrast, have about the same level of RS. At least, that’s the classic story we’ve been told since 1948. In their replication attempt, Gowaty and colleagues deemed this classic story was empirically unverified. It wasn’t true.

English geneticist Angus John Bateman

This could be a big deal for sexual diversity science. A lot of research and theory in biology has flowed more or less directly from Bateman’s original findings. In the annals of evolutionary biology, the presumption of sex differences in RS variance has become known simply as “Bateman’s Principle” (actually, several Bateman principles were derived from his work, including the important “Bateman gradient,” with sex differences in RS being Bateman Principle 1, sex differences in mating success being Bateman Principle 2, and sex differences in mating success being linked to sex difference in RS being Bateman Principle 3). But let’s stick here to just the Bateman Principle 1 on sex differences in RS variance. Bateman’s Principle 1 has served as a framework from which numerous theories have gone on to explain why males and females tend to differ in courtship behavior, mate choice, competitiveness, violence, mortality, and of course basic reproductive strategy. If Bateman’s original work is suspect, perhaps all of sex difference science is suspect! In the words of George Takei, oh myyy…

After the publication of this striking replication failure, media headlines followed such as “Biologists reveal potential 'fatal flaw' in iconic sexual selection study” and "So men aren't hard-wired to be unfaithful after all? Famous Forties study that claimed men are promiscuous by nature is found to be flawed." The sexual blogosphere went predictably nuts. Even some scientists renewed calls for serious doubt about evolved sex differences in mating strategies. Regrettably, such strong reactions to these new findings are largely unmerited, and many of the conclusions communicated by the media were misleading in several ways. Gowaty et al. (2012) is an important study, but it, too, has its limitations. Every study should know its limitations.

What Does the Research Really Show?

For one thing, Gowaty and colleagues left strangely unreported their actual data on sex differences in number of mates or variance in RS (as they noted in their "What We Did Not Do" section). They just assert it's not reliable data to begin with, as are Bateman's old methods (assuming this new study is an accurate replication). Fair enough, but it could be much more consequential as a scientific “failure of replication” if Gowaty and colleagues had reported literally no sex differences in variability of RS. Maybe they did find that, but we don’t know based on their reported research, which in sexual science is kind of weird. No data?

In any event, lots of data are available on sex differences in RS variances, over 60 years worth since Bateman, and the empirical evidence clearly shows males have higher RS variability across a wide variety of species (especially mammals; 97% or so of them). It is almost always the case that males have more RS variance than females, much as one expects from Bateman’s Principle. Of this there is little doubt.

Even so, there are important exceptions to Bateman. Sometimes a given species’ evolved mating strategy leads to smaller or negligible sex differences in RS variance (e.g., intensely selected genetic monogamy or heightened importance of paternity confusion). Still, when there are variations away from Bateman’s principle, these are not viewed by most biologists as somehow refutations of evolution or Darwin’s (1871) Sexual Selection Theory. Instead, extant evidence is often consistent with Trivers’ (1972) integrative Parental Investment Theory, including supportive findings of sex-role reversals of Bateman's Principle among pipefish (Jones et al., 1999). Among pipefish, females have more variance in RS, but they also invest less in their offspring and have less intense sexually-selected mate preferences than males of their species. They are exceptions to the general Bateman’s Principle rule.

This is key. Gowaty and her colleagues’ paper should be viewed as an important historical corrective to problems with Bateman’s original methods, much like problems have been identified with the original peppered moth studies documenting natural selection in action (Proffitt, 2004). Their paper is that important, no doubt. But contrary to media reports, their new findings fail to overturn decades of research on sex differences in RS variance from across animal kingdom. Every species is different, but the preponderance of evidence supports Bateman’s Principle no matter what happens with Drosophila melanogaster.

What about Humans?

In humans, there is near-universal evidence of greater RS variance in men than women. Brown et al. (2009) found greater RS variance in men across 94.4% of human societies for which there was reliable data, with a 1/1000 chance that RS variance in humans is the same in men and women across 18 societies, t(17) = 3.82, p < .001. Critically, Brown and colleagues found some societies have extremely high sex differences in RS variance, especially among those that live a foraging lifestyle similar to our Pleistocene ancestors. More recently, Betzig (2012) reported men’s RS variation was about twice women’s among the predominantly foraging Aché, Aka, Hadza, !Kung, and Meriam societies. Furthermore, as expected from Bateman men’s greater RS variance is more closely linked to their social status than is women’s (Hopcroft, 2006; Nettle & Pollet, 2008). Men also reach maturity later, die earlier, have larger size, and exhibit a host of psychological and physical features that, to put it frankly, suggest Bateman’s Principles are is relevant for understanding human sexual diversity (Alexander & Noonan, 1979; Geary, 1998).

Unlike many most animals, however, human mating strategies are rather flexible and facultative. How we go about mating depends on a whole lot more than just our biological sex, with local factors such as sex ratio variations, population density differences, sex-biased mortality levels, and the degree of socially-imposed monogamy affecting the intensity of sex differences in RS variances (see Brown et al., 2009). While Bateman’s Principles are likely relevant for humans (we are mammals, after all), there is a lot more to our evolved sexual psychology than just sex-linked or culture-linked differences in RS variance. Thinking that all human populations everywhere must show the exact same sex difference in RS variance if it is really "evolved" is cultural-invariance thinking that is one of the Toxic Tetrad of misunderstanding evolved sex differences across cultures.

Humans Are More than Bateman Principles

In the field of evolutionary psychology, for over two decades researchers have addressed the limitations of Bateman’s Principle as applied to humans. Esteemed scientists such as David Buss, Doug Kenrick, Martie Haselton, Steve Gangestad, and others have long emphasized the adaptive benefits of short-term mating among women (for a nice review, see Thornhill & Gangestad, 2008), as well as, the benefits of long-term and monogamous mating for men. They have pioneered the study of adaptive within-sex variations in attachment styles, life history strategies, and sexual strategies (see Buss, 2005). Evolutionary psychologists who study humans have blazed trails for more than 20 years in a post-Bateman world, leaving recent calls for moving “beyond Bateman’s Principle” in understanding human sexual diversity as, scientifically speaking, rather antiquated in tone.

Personally, I sure hope sexual scientists of the future don’t use the Gowaty et al. (2012) article as a historical platform for "debunking" the erroneous portrayal of evolutionists as thinking all males are promiscuous and all females are monogamous. It seems like the media can’t help themselves from blathering such pablum, but this simplistic characterization of evolutionary psychology is wrong in so many ways, it's hardly worth being called a straw man (see http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/sexual-personalities/201202/men-wom…). More like a spectre man (no offense to the actual Spectreman).

Update: The Spectreman of continuing attempts to refute Bateman applying at all to humans continues. For instance, in 2023 researchers dove deeply into population-wide samples of both married and cohabiting people from Finland (Andersson et al., 2023). Finland was the population that definitely failed to demonstrate greater RS in men and women in the older review by Brown et al. (2009), so it's a good choice to refute Bateman. With this updated population-wide research in Finland, however, they actually found that, yes, there is evidence in Finland for some of Bateman's Principles. But you probably haven't read that in the media. Let's go over what they found...

For Bateman's Principle 1 (i.e., men should be more variable that women in Reproductive Success, RS), it appeared that even in Finnish culture (with their relatively low fertility [about 1.8 children per woman], high contraception rates, and high gender equality; Andersson et al., 2023), some men seem to have lots of children, whereas some men have fewer children (compared to women, who are much less variable than men in number of children). This positive confirmation of Bateman Principle 1 applying to humans indicates there has been a greater opportunity for selection to act on men than women in Finland.

There was even support for Bateman’s Principle 2: Men will be more variable in Mating Success (MS) than women. The Finnish evidence suggested some Finnish men seem to have lots of mates, whereas some men have fewer mates…and critically women were much less variable in their number of mates than men were. This positive confirmation of Bateman Principle 2 applying to humans indicates that there is increased opportunity for sexual selection processes to act on men, compared to women, in Finland. Bateman's principles aren't doing too bad in Finnish humans, after all.

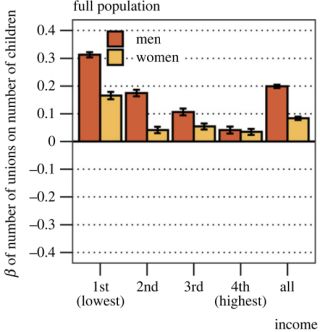

There was only limited support for Bateman’s Principle 3: In men there should be stronger links between MS and RS than among women. The Finnish evidence? The MS x RS links were more true of men from lower classes (see the below), with the fewest children being especially due to low status men having never had a mating partner (whereas low status men with many partners having had many children).

The researchers noted...“For men (but not women) in the lowest income quartile, having multiple unions positively predicts RS” (p. 7).

The authors of this study also concluded: “In the population as a whole, data suggest a positive relationship between number of unions and RS, and that this association is higher for men than women…this relationship is driven by ever forming a union rather than the number of unions” (p. 7). Indeed, they note that for 92% of Finnish people, MS was not linked to RS (for various reasons, including relatively low fertility all around).

So, overall, great evidence for Bateman's Principle's 1 and 2 in Finland. Principle 3 is more complicated. As the authors themselves note, "In the population as a whole, data suggest a positive relationship between number of unions and RS, and that this association is higher for men than women". So, that's support for Bateman being relevant to humans, right?

Well, among higher status men, having more mates didn't lead to more children, but having longer mateships did! If you're going to follow a long-term strategy in a nation with low fertility and high contraception, it might pay (in terms of fertility) to stay a long time with one partner. Interesting result! And another great addition to more than 30 years of evolutionary psychology moving beyond just Bateman.

References

Alexander, R.D., & Noonan, N.M. (1979). Concealment of ovulation, parental care, and human social interaction. In N.A. Chagnon & W. Irons (Eds.), Evolutionary biology and human social behavior: An anthropological perspective (pp. 402-435). North Scituate, MA: Duxbury.

Andersson, L., Jalovaara, M., Saarela, J., Uggla, C. (2023). A matter of time: Bateman’s principles and mating success as count and duration across social strata in contemporary Finland. Proc. R. Soc. B 290:

20231061. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2023.1061

Bateman, A.J. (1948). Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity, 2, 349-368.

Betzig, L. (2012). Means, variances and ranges in reproductive success: Comparative evidence. Human Behavior and Evolution, 33, 309-317.

Brown, G. R., Laland, K. N. & Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (2009). Bateman’s principles and human sex roles. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 24, 297-304. DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2009.02.005.

Buss, D.M. (2005). The handbook of evolutionary psychology. Hoboken: Wiley

Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray.

Geary, D.C. (1998). Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Gowaty, P.A., Kim, Y.-K., & Anderson, W.W. (2012). No evidence of sexual selection in a repetition of Bateman's classic study of Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1207851109.

Hopcroft, R.L. (2006). Sex, status and reproductive success in the contemporary United States. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 104–120.

Jones, A.G., Rosenqvist, G., Berglund, A., Arnold, S.J., Avise, J.S. (2000). The Bateman gradient and the cause of sexual selection in a sex-role-reversed pipefish. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 267, 677-680.

Nettle, D., & Pollet, T.V. (2008). Natural selection on male wealth in humans. American Naturalist, 172, 658-666.

Proffitt, F. (2004). In defense of Darwin and a former icon of evolution. Science, 304, 1894-1895.

Thornhill, R. & Gangestad, S.W. (2008). The evolutionary biology of human female sexuality. Oxford University Press: New York, NY.

Trivers, R. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.). Sexual selection and the descent of man: 1871-1971 (pp. 136-179). Chicago: Aldine.