Intelligence

What are the Key Dispositions of Good Critical Thinkers?

A collective intelligence analysis of critical thinking dispositions.

Posted January 18, 2016

As human beings, we make thousands of decisions every day. Every time we go to the shop to buy bread we must decide whether we would prefer white bread, brown bread, small or large loaf, barrel or sliced, etc. The same goes for the ‘simple’ task of ordering a coffee. For example, if you enter Starbucks, it’s been estimated that there are over 19,000 possible beverages available to you (Vohs et al., 2014). Indeed, we are immersed in increasingly complex and differentiated environments -- decisions are ever-present and surround us as we make our way in the world.

Of course, some decisions are more important than others. Perhaps ordering coffee at Starbucks and selecting bread at the shop are not seen as incredibly important by many people and, naturally, we often depend on prior choices or habitual responses to guide our choices in these situations. But what about decisions we care about, decisions that we recognise as important and that require some deliberation? Repeating habitual responses or ‘going with our gut’ in those situations will not suffice – we must pause for reflection and think critically – we must think about our decisions in these situations. Although it is not always clear what is needed to support good critical thinking, scholars have suggested that there may be a number of core personal dispositions that support good critical thinking. But what are these critical thinking dispositions?

Critical thinking (CT) is commonly defined as a metacognitive process, consisting of a number of cognitive skills (e.g. analysis, evaluation and inference) and a variety of personal dispositions (e.g. open-mindedness, inquisitiveness and scepticism), that, when used appropriately, increases the chances of producing a logical solution to a problem or a valid conclusion to an argument (Dwyer, 2011; Dwyer, Hogan & Stewart, 2012; 2014). However, most definitions of critical thinking (CT), and most interventions designed to increase CT, are grounded in academic or expert definitions of CT skills; and there has been very little emphasis on CT dispositions in the research conducted to date. Furthermore, students and educators are rarely, if ever, asked to describe their perspectives on what constitutes CT or key CT dispositions. As such, critical thinking dispositions have not yet been clearly conceptualised in research literature; and what little is agreed upon when it comes to such disposition is generally derived from the opinions of academics.

So what do students and educators describe as the key dispositions of good critical thinkers? We recently conducted research to address this question, as part of our ongoing efforts to develop and validate a new Critical Thinking Dispositions Scale. Using a collective intelligence methodology, Interactive Management, we examined the way students and educators conceptualise CT dispositions.

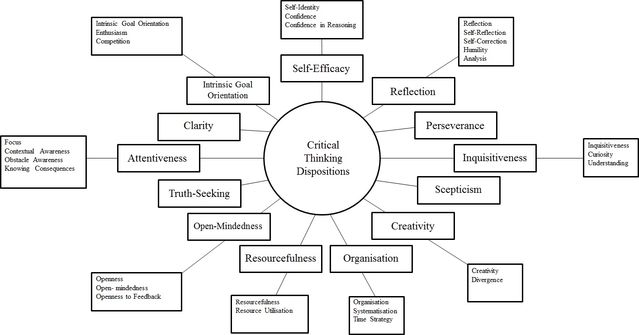

Interactive Management (IM) is a computer-assisted process that allows a group to build a structural model describing relations among elements in a system. In the current study, these elements were CT dispositions, and the relations of interest were the ways in which these dispositions support one another in a positive system of influence. Interactive Management is a five-step systems thinking methodology that is used to aid groups in developing outcomes that integrate contributions from individuals with diverse views, backgrounds and perspectives, via: (1) generating and clarifying ideas; (2) voting, ranking and selecting elements for structuring; (3) structuring elements by answering a series of questions in the form: “Does CT disposition A facilitate CT disposition B?’’; (4) evaluating a graphical representation of group logic; and (5) interpreting and evaluating discourse and reasoning to further understand the nature of the collective intelligence. In our study on critical thinking dispositions, three groups comprising a total of thirty-one students and ten educators took part in the collective intelligence workshops. Across these three workshops, a total of 32 CT dispositions were identified and organised into 13 categories (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Key Dispositions of Good Critical Thinkers

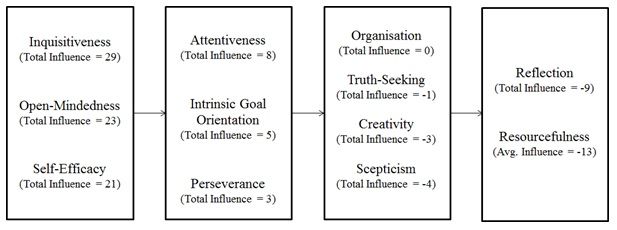

An analysis of the systems thinking of participants revealed that key CT dispositions including inquisitiveness, open-mindedness and self-efficacy had the strongest positive, supporting influence on other CT dispositions in the set; whereas, reflection and resourcefulness were seen as highly dependent on other dispositions (i.e., supported positively by other dispositions in the set). Drawing upon the logic of these systems structures, and ordering the full set of critical thinking dispositions by reference to their relative influence in the system, revealed the following ordered set:

- Inquisitiveness: An inclination to be curious; desire to fully understand something, discover the answer to a problem and accept that the full answer may not yet be known; a desire to understand a task and its associated requirements, available options and limits.

- Open-Mindedness: An inclination to be cognitively flexible, open to divergent or conflicting views; detaching from one’s own beliefs to consider diverse points of view without bias or self-interest; to be open to feedback, accepting positive feedback, criticism or constructive feedback with thoughtful consideration; an openness to amending existing knowledge in light of new ideas and experiences; and a willingness to explore new, alternative or ‘unusual’ ideas.

- Self-efficacy: The tendency to be confident and trust in one’s own reasoned judgments; acknowledging one’s sense of self while considering problems and arguments (i.e. situating reasoned judgements within one’s own life experiences, knowledge, biases, culture and environment); to believe in one’s ability to receive and internalize feedback positively and constructively; to be self-efficacious in leading others in the rational resolution of problems; and belief that good reasoning is the key to living a rational life and to a creating a more just world.

- Attentiveness: Willingness to focus and concentrate; to be aware of surroundings, context, consequences and potential obstacles; to have the ‘full picture’.

- Intrinsic Goal Orientation: Inclined to be enthusiastic towards a goal, task, topic of focus and, if not the topic itself, enthusiasm for the process of learning new things; to search for answers as a result of internal motivation, rather than an external, extrinsic reward system.

- Perseverance: To be resilient and to be motivated to persist at working through complex tasks and the associated frustration and difficulty inherent in such tasks, without giving up; motivation to get the job done correctly; a desire to progress.

- Organization: An inclination to be orderly, systematic and diligent with information, resources and time when determining and maintaining focus on a task, problem or question, whilst simultaneously considering the total situation and being able to present the resulting information in a holistic, organized fashion, for purposes of achieving specified goals.

- Truth-Seeking: A desire for knowledge and truth; to seek and offer both reasons and objections in an effort to inform and to be well-informed; a willingness to challenge popular beliefs and social norms by asking questions (of oneself and others); to be honest and objective about pursuing the truth even if the findings do not support one’s self-interest or pre-conceived beliefs or opinions; and willingness to change one’s mind about an idea as a result of the desire for truth.

- Creativity: A tendency to visualize and generate ideas; and to ‘think outside the box’ (i.e. think differently than usual)

- Skepticism: An inclination to challenge ideas and question conclusions in light of the evidence presented; to withhold judgment prior to engaging with the evidence; to take a position and be able to change position when the evidence and reasons are sufficient; and to look at findings from various perspectives.

- Reflection: An inclination to reflect on one’s behavior, attitudes, opinions, and motivations; to distinguish what is known and what is not; to approach decision-making with an awareness of limited knowledge or uncertainty, recognition that some problems are ill-structured, some situations permit more than one plausible conclusion or solution, and judgments must often be made based on analysis, evaluation, standards, contexts and evidence that preclude certainty.

- Resourcefulness: The willingness to utilize existing resources to resolve problems; search for additional resources in order to resolve problems; to switch between solution processes and knowledge to seek new ways/information to solve a problem; to make the best of the resources available; to adapt and/or improve if something goes wrong; and to think about how and why something went wrong.

Another way to understand this logic of supporting influence, or the relation between critical thinking dispositions, is by reference to the total influence map in figure 2, where dispositions to the left are collectively seen to influence disposition to the right. This figure represents a meta-analysis of the systems thinking across the three workshops, and highlights dispositions that influence or support other dispositions in the system.

Figure 2. Influence Map Describing Supporting Relations between CT Dispositions

Interestingly, one CT disposition, clarity, although highlighted as important during the idea generation stage (i.e., Step 1 above), did not receive a sufficient number of votes when it came to selecting ideas for structuring (i.e., Step 3 above). However, we believe it is important to highlight the significance of clarity, which was defined by our participants as the inclination to seek intelligibility, transparency, lucidity and precision, from oneself and others, and to be clear with respect to the intended meaning of what is communicated.

We appreciate that more work needs to be done to further understand the dynamics of critical thinking dispositions in action. We are currently working to develop critical thinking educational programmes that support the cultivation of key CT skills and dispositions. The understanding obtained through our collective intelligence research has also informed the development or a new Critical Thinking Dispositions Scale, which we are currently working to validate. We believe a new Critical Thinking Dispositions Scale is needed to empower students and educators who wish to reflect upon their critical thinking dispositions and negotiate new learning experiences that promote the development of CT skill and dispositions in academic settings. If you would like to contribute to our scale development work, we would be delighted if you could take our survey.

Link to Sona version of survey for NUI, Galway Students:

A direct link to survey is available upon request to michael.hogan@nuigalway.ie

Chris Dwyer (LinkedIn, ResearchGate), Michael Hogan (Web), Owen Harney (ResearchGate), Caroline Kavanagh, Sarah Quinn.

References

Dwyer, C.P., Hogan, M.J., Harney, O. & Kavanagh, C. (2016). Facilitating a student-educator conceptual model of dispositions towards critical thinking through interactive management. Educational Technology & Research (Submitted).

Dwyer, C.P. & Hogan, M.J. (2014). An integrated critical thinking framework for the 21st century. Thinking Skills & Creativity, 12, 43-52.

Dwyer, C.P., Hogan, M.J., & Stewart, I. (2012). An evaluation of argument mapping as a method of enhancing critical thinking performance in e-learning environments. Metacognition and Learning, 7, 219-244.

Dwyer, C.P., Hogan, M.J., & Stewart, I. (2011). The promotion of critical thinking skills through argument mapping. In C.P. Horvart & J.M. Forte (Eds.), Critical Thinking, 97-122. Nova Science Publishers, New York.

Vohs, K. D., Baumeister, R. F., Schmeichel, B. J., Twenge, J. M., Nelson, N. M., & Tice, D. M. (2014). Making choices impairs subsequent self-control: a limited-resource account of decision making, self-regulation, and active initiative.