Education

20 Years of LGBTQ Research in Education Part 2

Why is research not impacting policy and practice?

Posted May 6, 2013

The following post is Part 2 of 2. Read the first post here.

[*] Research production on LGBTQ issues in education really started gathering steam in the new millennium, enabling more nuanced and complex areas of study to emerge and greater attention to the gaps and silenced voices in the existing data: including students of color and transgender youth. There was an increasing influence of intersectional analyses and queer theoretical approaches. There was also a steady increase in successful litigation against school districts by GLBT youth and their advocates (Meyer 2007, 2009).

After three years back in the classroom in New Hampshire, during the 2000-2001 academic year I started a GLSEN chapter, planned a National Coming Out Day rally on the state house steps, and co-organized the first GLBT youth prom in the state. I also sat on an advisory committee at the state department of education as they were drafting a new bullying law. I advocated strongly for enumeration and tried using the 1999 GLSEN data to support that, but my efforts were unsuccessful. In August 2001, I left that school for a Fulbright exchange to teach English at a middle school in France. The day before I left the country, my dean informed me I would not be offered a contract upon my return the following year. It was clear that the notoriety my statewide activism was bringing to the school was a strong factor in that decision.

[*] So, I found myself back in graduate school in 2003. I started Doctoral work at McGill University in Montreal, and attended my 1st two AERA conferences. 2004 in San Diego was notable, because, I recall attending small meeting of the Lesbian and Gay Studies SIG where the name was changed to the Queer Studies SIG. Mary Lou Rasmussen reports that just 2 years earlier, it was a contentious idea that was quickly voted down. In 2005, I presented my first paper at the meeting in Montreal that discussed the Nabozny case, the Wagner case, and the Jubran case from British Columbia arguing for the importance of using these legal decisions to advocate for change in schools for LGBT youth (Meyer 2005).

[*] Now if we turn to how research has impacted policy, most policy changes seem to have come about as a result of lawsuits or individual tragedies – just think about all the new bullying laws that started emerging post-Columbine. Also consider, in 2010, the Office for Civil Rights issuing a “Dear Colleague” letter providing guidance for schools and districts regarding their responsibility re: Title IX stating that homophobic harassment and transphobic harassment are actionable under Title IX; even though that legal precedent had been established in the Wagner case in 1999. There is new legislation, the Student Non- Discrimination Act, that has been introduced that would explicitly add the categories of ‘sexual orientation and gender expression’ as protected classes in federally funded educational programs.

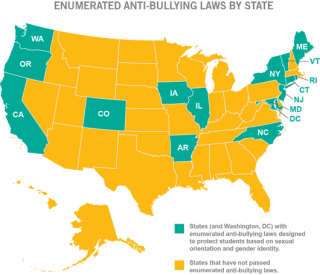

GLSEN's data on states with enumerated bullying policies

[*] Only 14 states currently have bullying policies that have enumerated categories, even though there is now a wealth of evidence to show that enumerated polices protect kids and reduces bullying. [*] Of greater concern is the eight states have “no promo homo” laws prohibiting the respectful inclusion of LGBT people and issues in schools. Even though research and multicultural educational theories tell us that erasing and ignoring students’ identities and experiences is a form of oppression and a significant barrier to learning. It prevents students from having meaningful opportunities for educational success, or “opportunities worth wanting”. So why isn’t this research having greater impacts on policy and practice? I offer three possible reasons:

- organized resistance

- fear

- lack of courage

First, there is strong organized resistance by the religious right against making our public schools sites that recognize and value the diverse, multicultural, and multilingual history of our country. Second, LGBT people and issues often spark unfounded fears that there will be explicit discussions of sexual behaviors in K-12 classrooms. The threat of open discussion of sexual and gender diversity can cause parents and community members to confront what they don’t know -- and don’t want to know -- about the diversity that already exists in communities all across this country. There is also limited understanding of what sexual diversity is; it includes issues related to family, identity, community, and relationships as well as behavior. Sexual behavior is just one aspect of sexuality.

Finally, there is a poverty of courage to do the right thing amongst school leaders, politicians, and professional associations – specifically AERA. [*] If we can’t seem to convince our own professional association to regard this research evidence as compelling enough to take action on, so how can we expect to convince anyone else? For example, there is a long history of AERA’s non-action on LGBT issues: including in 2007 when NCATE revised their rubrics for teacher education and removed “sexual orientation” from the categories evaluated; or in 2009 when the meeting was in San Diego and we asked that they withdraw sessions from the Manchester Hyatt due to Manchester’s financial support for Prop 8 and in solidarity with their workers who were already protesting their labor practices. These inactions are in stark contrast with the quick response to 2010’s AZ immigration law and the amicus brief filed in the Fisher v. University of Texas affirmative action case. In the AERA release, Executive Director Felice Levine is quoted as saying: “AERA has a fundamental interest in the accurate presentation of social science research on these important questions of law. Quite simply, we have a responsibility to enable the Court to make its determinations based on the best scientific evidence available,”

[*] This year, AERA did NOT file an amicus brief in the Prop 8/DOMA SCOTUS case when one of the key public discussions around Prop 8 was about its impacts on public schools and children. Many other professional associations such as the California Teachers' Association, American Psychological Association, American Bar Association, American Sociological Association all did. Also, AERA did initiate a project that aims to present a comprehensive overview of the research on LGBTQ issues in education. However, this report has been underway since 2009 with minimal updates and collaboration with the Queer Studies SIG. There is significant distrust around what will be produced and what action steps will follow when it is eventually released. This has been well documented in the blogs and publications by scholars including Cath Lugg, Bill Tierny, Connie North, Erica Meiners & Therese Quinn and is available to review on our Queer Studies SIG wiki.

Finally, two new pieces of federal legislation: the Student Non-Discrimination Act, which is modeled after Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (20 U.S.C. §§ 1681-1688), to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity and expression and provides legal recourse to redress such discrimination, and the Safe Schools Improvement Act which would federally mandate states to have fully enumerated bullying laws which could have large positive impacts on the lives of students in the 36 states that don't have protections. AERA has not signed on to co-sponsor either of these bills. They currently are sponsored by groups such as [*]: AAUW, the American Federation of Teachers, the ACLU, GLSEN, the NAACP, the National Association of School Psychologists, the National Association of Secondary School Principals, American Counseling Association, the National Council of La Raza, the NEA, and the National Women’s Law Center. Where is AERA? to quote Ani DiFranco, “your silence is violence”

I recently attendeda two-day conference in Quebec on homophobia [French language website]. There, the Provincial government has committed $7.1 million over 5 years in grants to community organizations who work to support LGBT people and address systemic homophobia and transphobia that was put into place based on recommendations from an ongoing task force on homophobia. QC also has a new provincial bullying law the enumerates various protected categories, including sexual orientation and gender expression, and requires each school board to revise their policies and appoint a person responsible to implement this policy. Additionally, the government has rolled out a public awareness campaign that clearly communicates that homophobia and transphobia are not acceptable, and we all need to take steps to unlearn internalized biases we have developed over time.

Here, in California, we passed two related laws last year: Seth’s Law – requires schools to enumerate their bullying policies and requires teachers to intervene; and The FAIR Education Act – which requires the inclusion of the contributions of LGBT people, people with disabilities, and Pacific Islanders in the K-12 social sciences curriculum. However, these are unfunded mandates with no additional support or guidance offered from the California Department of Education. GLSEN’s research they just presented 2 days ago on bullying policies emphasizes how important these future federal laws could be in shaping local anti-bullying policies and influencing the school climate for so many youth.

We need courage, allies, and strong leaders to help our research inform policy. When policy makers are making decisions uninformed by current research, or going against what the research tells us, we have an responsibility help them “make determinations based on the best scientific evidence available,” as stated by our Executive Director (Felice Levine).

I come to AERA every year because of the amazing scholars I meet here. The Queer Studies SIG has been an incredibly productive source of ongoing professional development and engaged scholarship. However, I believe that our professional association, which is the largest educational association in the world, should show more leadership showcasing this research so as to better inform current educational policy. Let us share what we know, and what we have worked hard to know, so that this research can save lives, and create educational opportunities “worth wanting”, and to improve the conditions for all students in our schools.

References

Jackson, J. (2001). Come Out, Come Out, Wherever You Are: A Synthesis of Queer Research in Education Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association.

Meyer, E. J. (2007, April 9-13). Bullying and harassment in secondary schools: A critical analysis of the gaps, overlaps, and implications from a decade of research. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

Meyer, E. J. (2013, April 30). 20 years of LGBTQ education research and policy: From poverties of knowledge to poverties of courage. Paper presented at the The Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA.