Sleep

But I'm Not Sleepy!

Are our circadian rhythms the result of evolution or social cues? Or both?

Posted November 5, 2012

One of my strongest memories from high school is the feeling of that extra hour of sleep when we fall back into standard time each autumn. After the first few weeks of school, and the mounting sleep debt of having to wake up at too early of an hour, having that extra hour of sleep felt exquisite. But the eventual transition back to Daylight Saving Time in the spring was excruciating. Losing that hour of sleep made school much more difficult – at least until my urge to sleep aligned with Daylight Saving Time. My circadian rhythm was generally not the same as the one that I needed to get through the school day without feeling sleepy. This situation made very apparent to me that it’s arbitrary when we start school and work, and that my need for sleep was often at odds with those decisions.

Our circadian rhythms are the result of complex interactions between our body and our environment, and are generally seen as the force that cues us to feel sleepy. On one side, we have the urge to be awake. On the other, the need to sleep. When one overtakes the other, sleep or wakefulness ensues. As we sleep, the need to sleep reduces, and our alerting functions take over – until the need for sleep builds up again and we head for bed. Scientists have suggested that circadian rhythms govern much more than our need for sleep, including our urge to defecate and our appetites. We can delay our need for sleep – or eating or defecating – temporarily, but we can’t defer it indefinitely.

In his book, The Promise of Sleep, William Dement recounts the case of Randy Gardner who stayed awake for eleven days – but we now know that anyone who stays up for too long starts to microsleep as their need for sleep forces them to rest, even while their eyes might be open. As much as we might fight it, our circadian rhythm shapes our sleep.

Many people would tell you that our circadian rhythms are innately tied to the environments we’ve evolved in, but that’s not strictly true. Over the millennia that humans have evolved, they’ve inhabited a number of diverse environments around the globe, all with their own light cues – in circumpolar regions, humans have lived in periods of prolonged night and day; in equatorial regions, humans have been exposed to roughly equal periods of night and day. Sleep, in both of these environments – and all of the environments in-between – has developed as both a social and biological response to these cues. We sleep when we’re tired, but we also tend to take to our beds when the nights are long and we have limited light and heat. This has resulted in a wide variety of sleeping schedules – from societies that favor a midday nap to those that favor a long night in bed. And, then there’s the United States, that tends to favor a short night in bed – eight hours or less – and no midday nap, except for the very young and the very old.

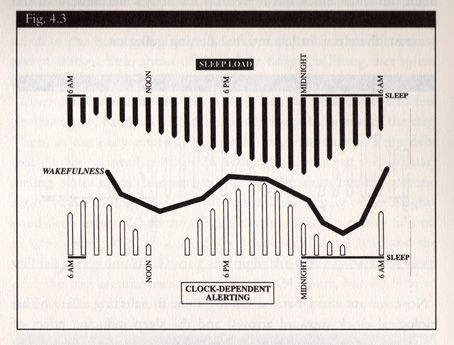

If you were to measure the circadian rhythms of people throughout the world, you should find that there are a wide variety of expressions of circadian cues. But when we look at the science of sleep, one representation of circadian rhythms prevails, and it often looks like this graph – which I’ve borrowed from Dement’s Promise of Sleep, and which I talk about extensively in my book, The Slumbering Masses.

Circadian Sleep Rhythms over a 24 Hour Period

This model is based on individuals sleeping for eight hours at night – from 10 p.m. until 6 a.m. But what if that individual took a nap in the middle of the day? Her sleep need would decrease accordingly and start to rise again. At bedtime, her sleep need would be less, but still enough to get to sleep. Or, if she slept in two four-hour blocks throughout the day, the need would be more balanced, and never so great that her urge overtakes her need – she wouldn’t just spontaneously fall asleep while in a meeting or driving home.

If we consistently slept in different patterns, our circadian rhythms would look quite different – both because of how we slept, but also because of other environmental cues, like food and light. Humans have evolved to have flexible circadian rhythms, and beyond just patterning of sleep shaping our rhythms, our exposure to light and our consumption of food shape our urges for sleep. This is one of the keys to understanding jetlag: when we go from one set of environmental cues to another, our bodies often react negatively, with our cues for sleep being mismatched to environmental cues. Only after we adjust to the new patterning of light and food intake do we begin to adjust to the new time zone, and our sleep follows suit. This can take a while, in part because our adjustment to food intake can be rather slow, whereas light impacts us quite quickly. Adjusting to Daylight Saving Time is often no big deal, because it’s a slight variance in time and we adjust our schedules accordingly. But adjusting to a bigger time difference – a few hours or more – can often leave us with a serve sense of being dislocated in time.

Despite the relative flexibility and variation of circadian rhythms, the models we have of our biological cues are fairly rigid and are based on the assumption of nightly consolidated sleep and large meals throughout the day. If we slept in two four-hour blocks, or one nightly block supplemented with a daily nap, our rhythms would alter. If we ate smaller meals throughout the day as well, our rhythms would again look less dramatic in their highs and lows. But such an organization of sleep and eating would depend on us investing in a much different ordering of society. The result would both be a dramatically different experience of sleep for us – as individuals and as members of society. And it would change how we conceive of normal and pathological sleep. What we now think of as sleep disorders – narcolepsy, insomnia, shift work sleep disorder – might not be so pernicious and in need of medical treatment.

But changing society to ease our discomforts around sleep seems unlikely – if it’s ever going to happen, it’s going to depend on denaturalizing our conceptions of human circadian rhythms and to take seriously how other orderings or society might benefit our biological experiences of ourselves and the world.