Humor

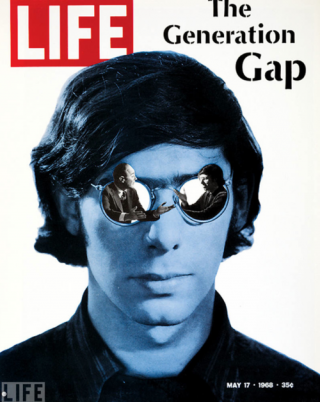

No More Generation Gap? Dream On

Boomers think we're closer to our kids than our parents were to us. But are we?

Posted January 20, 2014

Do Baby Boomers get along with our kids better than our parents got along with us? Most of us seem to think so. But most of us would probably be wrong.

When my younger daughter Samantha was 28, she and I spent a year writing a book together. (How's THAT for proof of how well Boomers and our kids get along? I never would have considered entering into a long-term project with Mom when I was 28.) As part of our research for the book, Twentysomething: Why Do Young Adults Seem Stuck?, Sam and I sent out questionnaires to more than 120 Millennials and Baby Boomers. Of the 31 questionnaires we got back from Baby Boomers, almost all mentioned that they themselves were closer to their kids than they had been to their parents.

“I don’t know exactly why but my relationship with my children is like night and day to my relationship with my parents,” Marji, a 60-year-old from suburban Washington, told us. “My parents and I fought about everything – when I came in at night, where I went, who I dated, what I wore, whether I was too fat, whatever.” But she said that her two sons, ages 32 and 28, have a totally different attitude. “They want to do things with us. They are happy to go on vacation with us, spend long weeks at the beach together, go out to dinner, etc. They are definitely part of our social life. I would not have wanted that with my parents.”

But are Marji and the rest of us fooling ourselves? Maybe a little.

Research has consistently shown that the older generation always feels closer to adult children (and even adult grandchildren) than the younger generation does, due to something called the Developmental Stake Hypothesis. Back in the 1960s and 1970s when we Boomers were young and thinking our parents didn't understand us, according to this hypothesis, our parents were probably thinking the parent-child relationship was fine. Now that it's our turn to be the middle-aged parents, maybe we're looking at the parent-child relationship with excessively rose-tinted glasses.

Noted sociologist Vern Bengtson of the University of Southern California and his colleague J.A. Kuypers first tried to explain this phenomenon in 1971. Middle-aged parents and their young-adult children are at different developmental stages, they wrote, and come to the parent-child relationship with different needs. The primary task for twentysomethings is to establish autonomy from their parents; they have a “stake” in making sure the relationship is none too cozy. For fiftysomethings, the task is what Erik Erikson called generativity, finding a way to pass on their knowledge, values, and nurturance to the next generation. So their “stake” is for the relationship to be loving and close. As a result, Bengtson and Kuypers wrote, parents “tend to overstate affectual and consensual solidarity with their offspring.” And the offspring, with their need to pull away, tend to understate it.

Interestingly, the same disparity in how parents and adult children view their relationship has been found even when parents and children are older – long after the parents have passed the generativity stage, long after the kids most vociferously need to assert their independence. Elderly parents tend to think their relationship with their middle-aged children is smoother than the children do. Adult grandchildren, who have little stake in pulling away from their grandparents, tend to describe that relationship as less rose-colored than do Gram and Gramps. So psychologists now call it the Intergenerational Stake Phenomenon, since factors other than one’s own developmental stage might also be at work in creating the imbalance.

More recently Kira Birditt of the University of Michigan, working with colleagues from Purdue and Penn State, made a related observation: that parents and adult children -- Baby Boomer parents and their Millennial children -- still manage to annoy the hell out of each other. They interviewed 158 families in Philadelphia, each consisting of a mother, a father, and a child over 22 who lived within 50 miles of the parents. They asked parents and kids what it was that bugged them about each other, and grouped the irritants into two categories: relationship tensions and individual tensions.

Kids’ complaints focused on relationship tensions: parents wanting more contact, offering unsolicited advice, intruding on their kids’ lives. This might have been because parents were more invested in the relationship, Birditt and her colleagues wrote in 2009, so they did things to try to make the relationship closer -- things that turned out to be annoying to their children. Parents, for their part, talked most about individual tensions, mentioning the myriad ways young people managed to fall short: job or education, finances, housekeeping, lifestyle, and health. Or, as the kids might have heard it: you’re poor, you’re messy, you eat crap, you drink too much, and when are you going to settle down and start a family already.

Mothers were found to be more annoying to (and more annoyed by) their daughters than their sons, and more annoying than fathers were to children of either sex. “Children feel their mothers make more demands for closeness,” the investigators wrote, “and they are generally more intrusive than fathers.”

Demanding and intrusive? Moi? Alright, alright, I admit it: my husband is the quiet, kind, accepting parent, and I’m the one who wants so much to be part of our two daughters’ lives than I can’t even let them finish a story without interrupting.

This all brings to mind a tart Saturday Night Live sketch from a few years back called "Damn It, My Mom is on Facebook." It's a fake commercial for a fake app that translates ordinary Facebook status updates into G-rated phrases appropriate for Mom to read. “There isn’t enough beer in the world for me to deal with Glenn Beck’s holy roller B.S.” magically gets posted on Mom’s wall as “Boy, do I need new dungarees.”

The mother in that sketch, played by guest host Jane Lynch in a Hallmark-sweet pink sweater, believes her Facebook activity gives her insight into her son's twentysomething life. She's delighted to be in his network, cheerily typing back on his wall about the "dungarees," “I’ve got a $5 coupon from Kohl’s. I’ll send it to you.” Cut away to the kids back in the dorm room, snickering about how cleverly they put one over on Mom.

To the Boomer parent of a twentysomething, there's an edge to the humor.

Adapted from Twentysomething: Why Do Young Adults Seem Stuck? by Robin Marantz Henig and Samantha Henig (New York: Hudson Street Press, 2012).