Intelligence

Why It's Dangerous to Label People

Why labeling a person "black," "rich," or "smart" makes it so.

Posted May 17, 2010 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

If you lined up 1000 randomly selected people from across the earth, none of them would share the exact same skin tone. You could arrange them from darkest to lightest and there wouldn't be a single tie. Of course, the continuity of skin tone hasn't stopped humans from assigning each other to discrete skin-color categories like black and white—categories that have no basis in biology but nonetheless go on to determine the social, political, and economic well-being of their members.

Categorical labeling is a tool that humans use to resolve the impossible complexity of the environments we grapple to perceive. Like so many human faculties, it's adaptive and miraculous, but it also contributes to some of the deepest problems that we face.

Researchers began to study the cognitive effects of labeling in the 1930s when linguist Benjamin Whorf proposed the linguistic relativity hypothesis. According to his hypothesis, the words we use to describe what we see aren't just idle placeholders; they determine what we see. According to one apocryphal tale, the Inuit can distinguish between dozens of different types of snow that the rest of us perceive, simply, as "snow," because they have a different label for each type. The story isn't true (the Inuit have the same number of words for snow as we do), but research by cognitive psychologist Lera Boroditsky and several of her colleagues suggests that it holds a kernel of truth. Boroditsky and her colleagues asked English and Russian speakers to distinguish between two similar but subtly different shades of blue.

In English, we have a single word for the color blue, but Russians divide the spectrum of blue into lighter blues (goluboy) and darker blues (siniy). Where we use a single label for the color, they use two different labels. When the two shades of blue straddled the goluboy/siniy divide, the Russian speakers were much quicker to distinguish between them, because they had readily available labels for the two colors that the English speakers lumped together as blue.

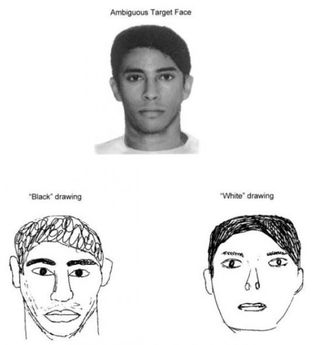

Labels shape more than our perception of color; they also change how we perceive more complex targets, like people. Jennifer Eberhardt, a social psychologist at Stanford, and her colleagues showed white college students pictures of a man who was racially ambiguous; he could have plausibly fallen into the white category or the black category. For half the students, the face was described as belonging to a white man, and for the other half, it was described as belonging to a black man.

In one task, the experimenter asked the students to spend four minutes drawing the face as it sat on the screen in front of them. Although all the students were looking at the same face, those who tended to believe that race is an entrenched human characteristic drew faces that matched the stereotype associated with the label (see a sample below). The racial labels formed a lens through with the students saw the man, and they were incapable of perceiving him independently of that label.

Race isn't the only label that shapes perception. A classic study by John Darley and Paget Gross showed similar effects when they varied whether a young girl, Hannah, seemed poor or wealthy. College students watched a video of Hannah playing in her neighborhood, and read a brief fact sheet that described her background. Some of the students watched Hannah playing in a low-income housing estate, and her parents were described as high school graduates with blue-collar jobs; the remaining students watched Hannah behaving similarly, but this time she was filmed playing in a tree-lined middle-class neighborhood, and her parents were described as college-educated professionals.

The students were asked to assess Hannah's academic ability after watching her respond to a series of achievement-test questions. In the video, Hannah responded inconsistently sometimes answering difficult questions correctly and sometimes answering simpler questions incorrectly. Hannah's academic ability remained difficult to discern, but that didn't stop the students from using her socioeconomic status as a proxy for academic ability. When Hannah was labeled "middle-class," the students believed she performed close to a fifth-grade level, but when she was labeled "poor," they believed she performed below a fourth-grade level.

The long-term consequences of labeling a child smart or slow are profound. In another classic study, Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson told teachers at an elementary school that some of their students had scored in the top 20% of a test designed to identify academic bloomers—students who were expected to enter a period of intense intellectual development over the following year. In fact, the students were selected randomly, and they performed no differently from their unselected peers on a genuine academic test.

A year after convincing the teachers that some of their students were due to bloom, Rosenthal and Jacobson returned to the school and administered the same test. The results were astonishing among the younger children: the "bloomers," who were no different from their peers a year ago, now outperformed their unselected peers by 10-15 IQ points. The teachers fostered the intellectual development of the bloomers, producing a self-fulfilling prophecy in which the students who were baselessly expected to bloom actually outperformed their peers.

Labeling isn't always a cause for concern, and it's often very useful. It would be impossible to catalog the information we process during our lives without the aid of labels like "friendly," "deceitful," "tasty," and "harmful." But it's important to recognize that the people we label as "black," "white," "rich," poor," smart," and "simple," seem blacker, whiter, richer, poorer, smarter, and simpler merely because we've labeled them so.

References

Carroll, J. B. (ed.) (1997) [1956]. Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. Cambridge, Mass.: Technology Press of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Darley, J.M., Gross, P.H. (1983). A hypothesis-confirming bias in labeling effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 20-33.

Eberhardt, J. L., Dasgupta, N., & Banaszynski, T. L. (2003). Believing is seeing: The effects of racial labels and implicit beliefs on face perception. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 360-370.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1992). Pygmalion in the classroom: Expanded edition. New York: Irvington

Winawer, J., Witthoft, N., Frank, M. C., Wu, L., Wade, A., & Boroditsky, L. (2007). The Russian blues: Effects of language on color discrimination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 7780-7785.