Suicide

Suicide Health Literacy: Do You Know When to Seek Help?

Everybody must know the suicide warning signs and what to do.

Posted May 12, 2024 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Suicidal thoughts are not that unusual. However, they may develop into life-threatening plans and actions.

- Everyone should know the warning signs of a suicidal crisis and when to seek help.

- Seeking help is a sign of resilience and strength.

Mental or psychological pain can be worse than physical pain. People often experience it as an existential threat, where the core beliefs of our sense of identity are at stake.

This acute mental experience activates the alarm system, and our brain wants us to end this painful condition. It may make us believe that suicide is the only solution.

From hundreds of interviews with people who survived a suicide attempt, I came to the conclusion that the vast majority of people who die by suicide would regret what they had done. This is why I advocate that basic knowledge about suicide and the warning signs must be general knowledge, similar to the knowledge about acute chest pain. In both cases, there is help available to be safe and stay alive.

How Suicidal Thoughts Can Turn Into a Dangerous Suicidal Action

Let’s start with a case example: Mr. K., aged 56, married, with two daughters, developed problems with chronic physical pain, which seriously impaired his work. He was a dedicated heating engineer, self-employed, and was proud of the reputation his business had achieved.

After two years of unsuccessful treatment of his pain, he began to weigh the pros and cons of suicide. He made an appointment with a psychiatrist, who diagnosed depression and referred him to psychiatric inpatient treatment. After discharge, his wife worked on him to give up his business, which she saw as the cause of his health problems. In a heated argument, his 28-year-old daughter joined up with her mother, criticizing him for having failed as a father because his business had always been his first priority.

The unexpected assault by his favorite daughter was “like a stab into the heart.” He went out into the garden and lit a cigarette. “It made a click” in his head and he knew that the next day he would end his life.

He had dinner with his wife, watched TV, slept all night, had breakfast with his wife, and then left, claiming he had some errands to do. He felt totally calm. It was a cold winter, with temperatures below minus 10 degrees Celsius. He drove up to the mountains, parked his car in a forest, and took an overdose of 42 painkillers together with a bottle of heavy liquor, which he thought would do the job together with the freezing temperature.

He was found the next day, lying in the snow, by someone who had noticed the empty car. He regained consciousness at the hospital after two days.

He was admitted to a psychiatric hospital from where he was referred to me for the Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program (ASSIP) [1]. In the first session, I asked him to tell me the story behind this serious suicide action. In the second session, we watched the video-recorded interview. Mr. K. was glued to the screen.

Suddenly, he said, “I am shocked how cold-blooded and indifferent I was. The moment I had made the decision it was like I was in a tunnel—no thoughts to the right, no thoughts to the left. It was like a PC where you press 'enter' and then a program runs by itself.”

Two years later, when he developed suicidal thoughts again, he drove to the psychiatric hospital he knew from the previous admission. He told them, “You have to take me in, I’m suicidal”. More than thirty years later, he is alive and doing well (case example from “The Suicidal Person”[2]).

What We Can Learn From This Case Example

- Mr. K. had big life goals: To be a reliable and highly respected engineer, available 24/7, to provide security to his family, and to be a good father (he was the son of a farmer who had little time for his children).

- Mr. K. had been considering suicide earlier as a solution when the physical problems interfered with his work. At that time, he had also considered the suicide method he would use.

- The actual suicide trigger was “the stab into the heart” by his beloved daughter, when she criticized him for having failed as a father. This resulted in what I call “unbearable existential pain.”

- During the ASSIP sessions, he realized that from the moment he decided to end his life, he had been running on an auto-pilot program (the “suicidal tunnel”) that nearly ended in death. He said: “This is frightening; I never want to get into such a mental condition again.”

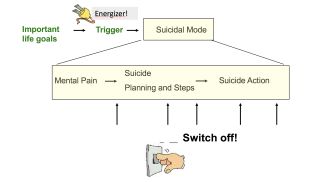

To conclude, we can put this into a short “suicide formula” which includes the following elements:

- thoughts about suicide as an option in a difficult life situation

- a triggering experience that deeply hurts and that is perceived as a threat to one’s very personal values

- high emotional stress that activates the alarm system

- thoughts and plans to end this unbearable mental state

- a switch of the brain function to a mental state in which we are acting like a robot, automatically carrying out the suicide plan

Most People Who Die By Suicide Would Regret What They Had Done

How do I know? In our ASSIP programs, we have interviewed several hundred patients, and it was obvious that these people, when describing the suicidal action, found themselves in a mental condition in which they were driven by their alarm system to end the unbearable state of mind. It is called the suicidal mode [3], a mental state where we can no longer think rationally and where we are unable to see the present crisis in a wider context. (For more about the suicidal mode, go here.)

Mr. K. was lucky to be given a second chance. The insight gained in ASSIP, an ultra-brief therapy protocol, helped him to be safe when two years later, he got again into a suicidal crisis. This corresponds with the results of the ASSIP study [4], where we found that in a 24-month follow-up, 60 ASSIP-treated patients had a total of five suicide reattempts, compared to 41 reattempts in the patient group who had received treatment as usual. In ASSIP, people realized that they could switch off the suicidal development at any time.

Here is what people had learned in the ASSIP sessions:

- When talking about the suicidal crisis, they realized that in the moment of harming themselves, they were acting in the suicidal mode.

- They recognized their suicide triggers which activated the suicidal mode.

- They made a list of their warning signs.

- They made a list of their strategies for how to switch off the suicidal roller-coaster.

- They carried these lists on them all the time.

What About You?

If you are a person who has experienced suicidal thoughts in the past, ask yourself:

- Do you know your suicide trigger?

Suicide triggers are experiences that deeply hurt us and that activate our inner alarm system. High emotional stress may make us panic and think that this unbearable mental state will never subside. Typical triggers are feeling rejected, abandoned, or humiliated; failing at an important life goal; feeling useless, etc.

- Do you know the warning signs of suicidal emotional stress?

Typical thoughts are “I’m worthless/useless, I am a failure, I have no right to live, I am a burden for others, the others would be better off without me, things will never get better, ending my life is the only solution.”

Typical body symptoms are agitation, dizziness, tightness in the chest, shortness of breath, palpitations, heart racing, etc. Typical emotions are panic, desperation, self-hate, and shame.

- Do you know the strategies that can help you to be safe?

Try to remember what strategies helped you in the past to cope with difficulties in life. These could include physical activity (biking, jogging, etc.), walking in nature (even in the rain!), or talking to a trusted person: a friend, family member, teacher, counselor, family doctor, or priest.

When things become critical, call a crisis line, a therapist, a family doctor, an ambulance, or go directly to the ED of the nearest hospital.

Summary

Suicide health literacy means that you have a basic knowledge of how a suicidal crisis can develop and when suicidal thoughts are especially dangerous. Be aware that under extreme emotional stress and pain, the brain may try to convince us that the only solution is to end it all. Suicide may appear to be a friend, but in fact, it is a false friend.

When you understand all this, you will be in a better position to pull the emergency stop before the suicidal mode (tunnel thinking!) takes over. Overcoming one’s own barriers and talking to someone is probably the main strategy. Try it!

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, seek help right away. For immediate help in the U.S., 24/7: Call 988 or go to 988lifeline.org. Outside of the U.S., visit the International Resources page for suicide hotlines in your country. To find a therapist near you, see the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Create your own safety plan: https://www.lifeline.org.au/get-help/beyond-now/create-your-beyond-now-suicide-safety-plan-online/

See also https://konradmichel.com/suicide-warning-signs-and-safety-strategies/

1. Michel, K. and A. Gysin-Maillart, ASSIP - Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program. A manual for clinicians. 2015, Göttingen: Hogrefe Publishing.

2. Michel, K., The Suicidal Person. A New Look at a Human Phenomenon. 2023, New York: Columbia University Press.

. Rudd, M.D., The Suicidal Mode: A Cognitive‐Behavioral Model of Suicidality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 2000. 30(1): p. 18-33.

4. Gysin-Maillart, A., et al., A Novel Brief Therapy for Patients Who Attempt Suicide: A 24-months Follow-Up Randomized Controlled Study of the Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program (ASSIP). PLoS Med, 2016. 13(3): p. e1001968.