Career

An Imbalanced Balance

A different way to assess your “work-life balance.”

Posted September 28, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Judging our balance by time devoted to the components of our lives will lead to stress and disappointment.

- Balance is best gauged by considering our degree of engagement with the things that matter most to us.

- Graphing our engagement in the important components of our lives can help us assess and attend to our balance.

"Balance,” as a stated goal in life, seems to be on the lips of everyone, particularly the young. And more power to them. Rather than a sign of sloth or lack of ambition, it’s a sign of emotional intelligence and self-compassion. But there’s risk in gauging one’s balance solely by the time devoted to the various components of one’s life.

Most jobs still demand six-to-eight hours of our days (and often a lot more). Hopefully, sleep takes up another eight. "Activities of daily living” (eating, shopping, meal preparation, commuting, laundry, cleaning, hygiene, etc.) may take up to six. How much does that leave for the things that really matter to us in life (those that bring us meaning, joy, contentment, and fulfillment)?

Fixate on, ruminate about, and struggle against this dynamic, and we become ensnared in an endless spiral of stress and despair. Every additional minute at work, every traffic jam, every line at the supermarket seems like an assault on our balance and, thus, on our beings.

A Different Way

Instead of appraising our balance by fretting over the time (or lack thereof) spent in the most valued components of our lives, we advocate instead, periodically assessing how successful we are at engaging in said components—that is, appraising how much of ourselves we are investing in the various relationships, activities, and experiences that really mean something to us. To visualize this better, try an exercise that has worked well for me and many others:

Make a list. Start by jotting down five to eight components in your life that are very important to you—that is, they bring you meaning, a sense of community, happiness, satisfaction, fun, love, joy, laughter, and the like. Hopefully, you will include activities/goals/people/experiences from both your home and work lives (see adjacent example).

Make a graph. Now, create a bar graph. On the X axis, make space for those five-to-eight highly valued components. On the Y axis, make a 0-to-10 scale representing your relative engagement in each of these components—perhaps with the 0 representing the sentiment: “I’m doing miserably at this” and 10 representing: “I'm knocking this out of the park" (see example below).

Plot out the graph. Then, rate your success on the Y axis for each of the components and plot them as bars on the graph. Don’t make your judgment predicated on time spent in these components but on your sense of success in engagement in them, attention to them, and deriving of fulfillment from them (see example below).

Review the results. If you try this exercise, you will most likely see that you are doing great in some of your valued components but may be doing poorly or sub-par in others. The graphing makes it vivid and draws your attention to the aspects of your life that could do with a little more of you—your attention, your focus, your energy, your thoughts, your creativity, etc. More time is rarely the answer. You may find that you spend plenty of time with a loved one, but that you don’t fully engage. Perhaps you spend the time “fire-gazing” at the television or scrolling through social media sites on your phone.

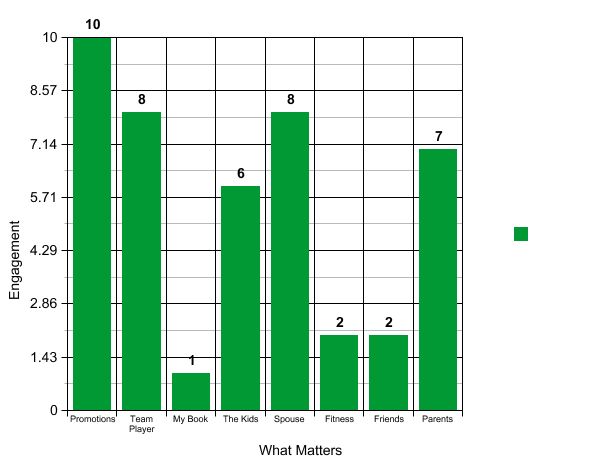

Example Graph

Take a look again at my example graph. Note how my engagement in writing a book is struggling. Giving this some thought, I may recognize that the activity just isn’t that important to me after all—at least at this time. Perhaps I might even shelve the project for now so I don’t constantly stress over it. Or, if I still deem it a critical component in my life, it becomes clear to me that I’m going to have to find a way to invest a lot more of myself in it.

Consider how I am also lagging with my commitment to fitness and my desire to see friends. The graph tells me that I’m going to have to invest more of myself in both aspects to establish that elusive sense of balance. Perhaps I could combine the two—start hitting the gym regularly with a couple of my best friends. And maybe I could find aerobic ways to play with my kids—because I’d like to do better in that category as well.

Go Ahead, Try It

Give the exercise a whirl: List your components; create your graph. Don’t spend hours setting the bar heights—they are relative assessments, not absolute measures. Be honest with yourself, though. How are you really faring in those components?

Now, reflect on it. If certain components are lagging, develop creative strategies on how to invest more of yourself in them. Then, redo the graph in a couple of months to see how you’re coming along.

If all your bars are pegged at the top, congratulations: You’re living a remarkably balanced life. But don’t rest on your laurels. Life is dynamic. Things change. Your life changes—as will your priorities, interests, and aspects that bring you a sense of fulfillment. Don’t be afraid, therefore, to change out various components over time and/or split some into smaller sub-components.

Through this exercise, you’ll come to recognize that eliminating a focus on time will be a huge step in addressing your worries about balance in your life and will allow you to better focus your energies on the drivers of your sense of imbalance.

References

Simonds, G., Sotile, W. (2019) Thriving in Healthcare: A Positive Approach to Reclaim Balance and Avoid Burnout in Your Busy Life. Huron Consulting Group, ISBN-10: 1622181085

Simonds, G., Sotile, W. (2018) The Thriving Physician: How to Avoid Burnout by Choosing Resilience Throughout Your Medical Career. Huron Consulting Group, ISBN-10: 1622181018

Lupu, I., Ruiz-Castro,M., (2021). Work-Life Balance Is a Cycle, Not an Achievement. Harvard Business Review. January 29, 2021. https://hbr.org/2021/01/work-life-balance-is-a-cycle-not-an-achievement

Bajaj, A., (2018). Work/Life Balance: It Is Just Plain Hard. Ann Plast Surg. 2018 May;80(5S Suppl 5):S245-S246. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001415.PMID: 29596086

Evans, E., Young, G., (2017). Work-life balance and welfare. Australas Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;25(2):168–171. doi: 10.1177/1039856216684736. Epub 2017 Jan 10. PMID: 28068830